ROLE OF MUSSELS IN THE ECO-SYSTEM

- They allow light to reach underwater plants, because they rid water of sediment, mud, or “suspended solids”

- They can naturally cleanse the water of algae threby eradicated its anaerobic effects

- They strengthen streambeds by keeping soils in place

- Invaluable to scientists as they indicate the long-term health of streams through their presence and overall health

- They provide a long lasting water solution to water clarity via the filtration they contribute because they can live up to a century.

- Each mussel can filter up to 20 gallons of water per day. One mussel bed studied in Southeast Pennsylvania was found to remove 26 metric tons (the weight of 5 or more elephants!) of solids from the water in a single summer season!

- They remove pathogens like viruses and bacteria from water

- Nestled among the bottom they provide habitat for other creatures, like small fish

- They are a source of food for wildlife, like muskrats, otters, raccoon, geese, ducks

- They enrich aquatic habitats – with their excrement

DELAWARE ESTUARY MUSSELS

Once plentiful in both numbers and species, freshwater mussels are now endangered and face an uncertain future in our local streams and rivers. Approximately 12-14 native species once lived in streams that drain to the tidal Delaware River. But today only one freshwater mussel species is easily found in these waters, and they are not often found in large numbers. Most streams that were once home to giant beds of mussels now have none at all. The decline is due to the combined effect of a myriad of things. Polluted water, toxic spills, loss of forests along streams, loss of fish hosts needed for reproduction all play a role in the loss of freshwater mussel species and populations.

THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL:

Freshwater mussels have a complicated life cycle which is tightly linked to freshwater fishes. Males release sperm into the water and the sperm are drawn in by the females. The fertilized eggs are brooded in the female’s gills where they develop into tiny larvae called glochidia. The glochidia are then released by the female mussels and attach to fish gills or skin as temporary parasites. To improve the larvae’s chances of contacting a suitable host fish, many mussel species have evolved elaborate methods to lure fish to the pregnant females. Females display and actively move their mantle lures to attract the host. When a fish strikes the lure, glochidia are released and attach to the fish. Many freshwater mussels have distinctive fish hosts. While some mussels depend on salamanders to distribute their young, the most common freshwater mussel in the Delaware Estuary depends on the American Eel.

AMERICAN EEL AS HOST FISH

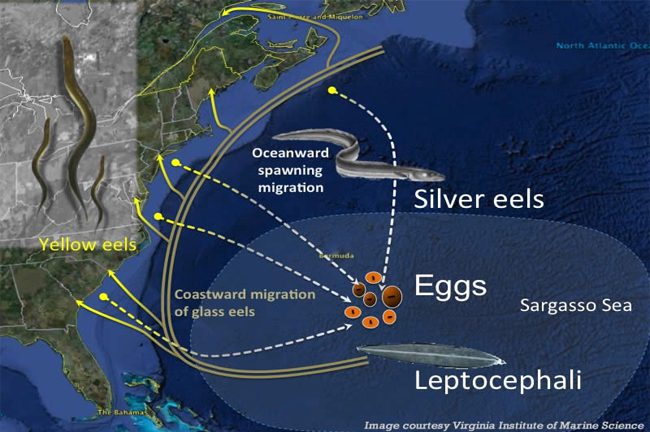

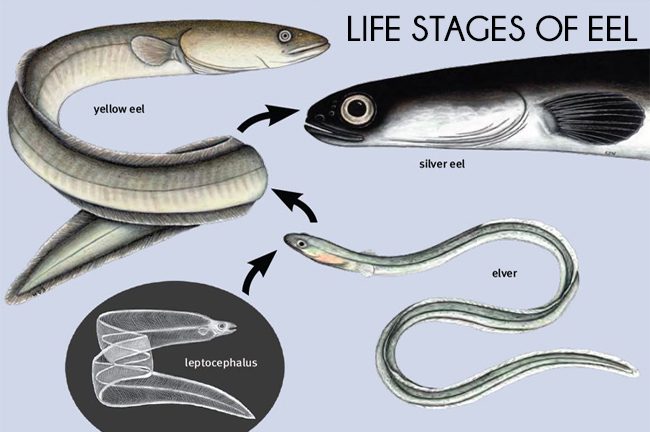

The remaining freshwater mussel of the Delaware Estuary is distinctive because its host fish is actually an eel, the American Eel (also known as the Atlantic Eel). This Eel, much like the mussel has a fascinating life cycle. It is born in the Sargasso Sea but then migrates to brackish and freshwater where it reaches maturity. Once reaching maturity (which can take up to 40 years in freshwater) it swims back to the Sargasso to spawn and its body adapts to be able to do so. Unfortunately, American Eels have become very low in number due to water dams which do not permit it to freely move to freshwater and rising nutrients from drainage sites which inhibit it venturing into shallower waters. This inability to move freely throughout the waters has depleted its numbers substantially, the Fish and Wildlife Service in Maryland estimates that between 1994 and 2004 the population has declined by 50%.

EEL RESTORATION

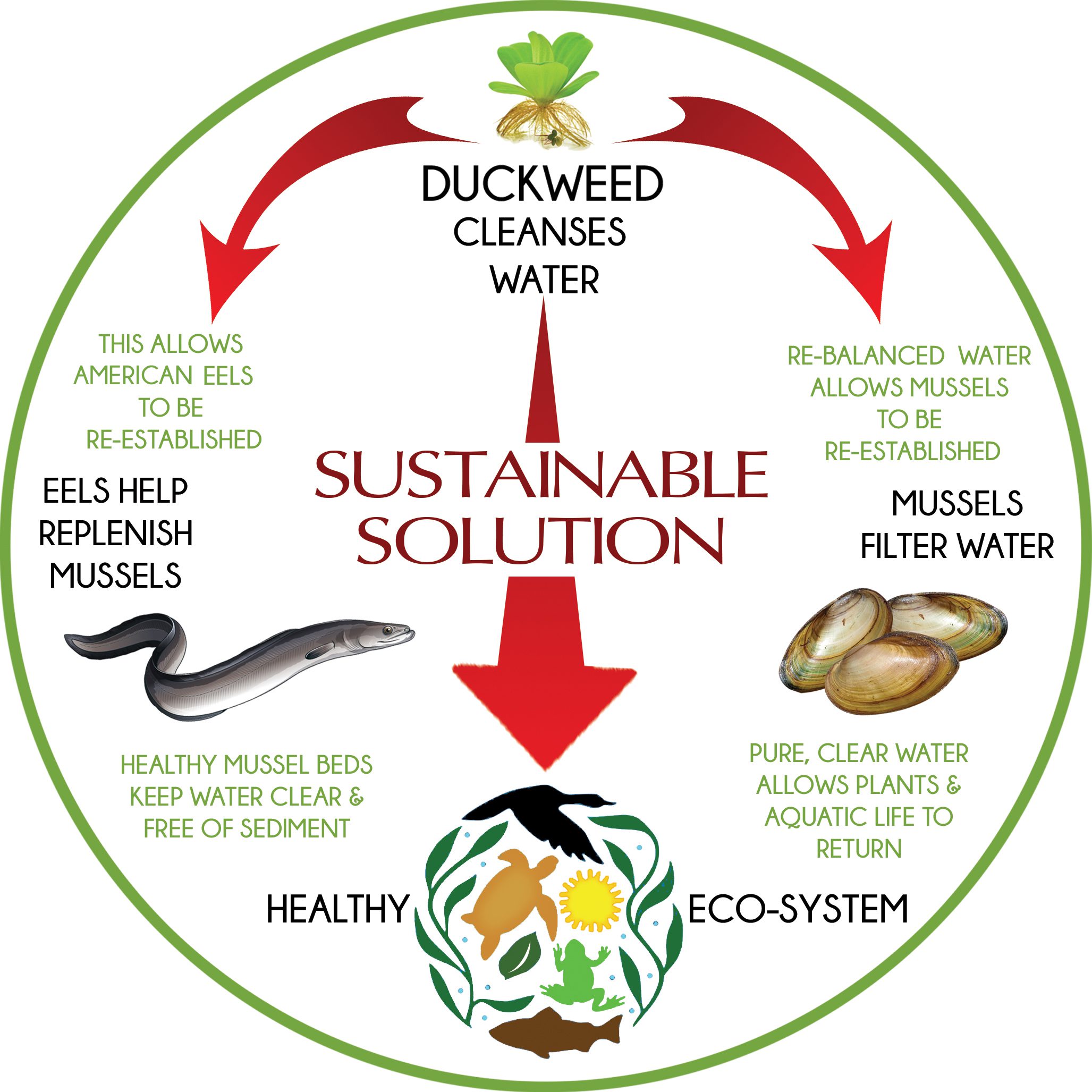

Luckily, there are several organizations which are restocking the waters with eels such as the Restoration Project which is currently going on in the Susquehanna River Basin, once a prime eel fishing ground, where an estimated 800,000 juvenile eels infested with mussel larvae have been released.. Since 2008, scientists have been helping eels bypass some of the dams as noted in the Bay Journal, “Mussels Could Up a Creek without Migratory Eels”. The Fish and Wildlife Service in Maryland has also been studying the symbiotic relationship between eels and mussels and have also been releasing eels infested with mussel larvae into the rivers to assist with mussel re-population. This can be a truly positive change and can have reverberating effects for the better throughout the estuary water if only the water nutrient level in the shallower waters can be re-balanced and maintained. Thus, the last link in the puzzle is establishing duckweed filtration stations which will purify these estuary waters so the good work of re-population can become self-sustainable.

HOW WE CAN RE-ESTABLISH MUSSEL COLONIES

The first and foremost thing needed is to create nutrient balance in the water. The estuary water has excess nutrients, from faulty septic systems, over-fertilization of lawns and agricultural run off. Since the mussels filter water through their bodies continuously they are very sensitive to this change in water composition. Birdsong Gardens, after extensive research, has formed the Water Clarity Project. Its goal is to use duckweed, a small aquatic plant, which removes Phosphates, Nitrates and other metals naturally from the water which would allow mussel colonies to be re-established in the estuary. Birdsong Gardens hopes to combine their efforts with local mussel hatcheries as well as Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University to repopulate the mussel population both by planting juvenile mussels and by releasing eels infested with mussel larvae into the waters. Once mussels begin to filter the sediment out of the water, their host fish, the American Eel, will be able to be re-established as well, securing the mussel beds for years to come.

ROLE OF MUSSELS IN THE ECO-SYSTEM

- They allow light to reach underwater plants, because they rid water of sediment, mud, or “suspended solids”

- They can naturally cleanse the water of algae threby eradicated its anaerobic effects

- They strengthen streambeds by keeping soils in place

- Invaluable to scientists as they indicate the long-term health of streams through their presence and overall health

- They provide a long lasting water solution to water clarity via the filtration they contribute because they can live up to a century.

- Each mussel can filter up to 20 gallons of water per day. One mussel bed studied in Southeast Pennsylvania was found to remove 26 metric tons (the weight of 5 or more elephants!) of solids from the water in a single summer season!

- They remove pathogens like viruses and bacteria from water

- Nestled among the bottom they provide habitat for other creatures, like small fish

- They are a source of food for wildlife, like muskrats, otters, raccoon, geese, ducks

- They enrich aquatic habitats – with their excrement

ESTUARY MUSSELS

Once plentiful in both numbers and species, freshwater mussels are now endangered and face an uncertain future in our local streams and rivers. Approximately 12-14 native species once lived in streams that drain to the tidal Delaware River. But today only one freshwater mussel species is easily found in these waters, and they are not often found in large numbers. Most streams that were once home to giant beds of mussels now have none at all. The decline is due to the combined effect of a myriad of things. Polluted water, toxic spills, loss of forests along streams, loss of fish hosts needed for reproduction all play a role in the loss of freshwater mussel species and populations.

THE LIFE CYCLE OF THE FRESHWATER MUSSEL:

Freshwater mussels have a complicated life cycle which is tightly linked to freshwater fishes. Males release sperm into the water and the sperm are drawn in by the females. The fertilized eggs are brooded in the female’s gills where they develop into tiny larvae called glochidia. The glochidia are then released by the female mussels and attach to fish gills or skin as temporary parasites. To improve the larvae’s chances of contacting a suitable host fish, many mussel species have evolved elaborate methods to lure fish to the pregnant females. Females display and actively move their mantle lures to attract the host. When a fish strikes the lure, glochidia are released and attach to the fish. Many freshwater mussels have distinctive fish hosts. While some mussels depend on salamanders to distribute their young, the most common freshwater mussel in the Delaware Estuary depends on the American Eel.

AMERICAN EEL AS HOST FISH

The remaining freshwater mussel of the Delaware Estuary is distinctive because its host fish is actually an eel, the American Eel (also known as the Atlantic Eel). This Eel, much like the mussel has a fascinating life cycle. It is born in the Sargasso Sea but then migrates to brackish and freshwater where it reaches maturity. Once reaching maturity (which can take up to 40 years in freshwater) it swims back to the Sargasso to spawn and its body adapts to be able to do so. Unfortunately, American Eels have become very low in number due to water dams which do not permit it to freely move to freshwater and rising nutrients from drainage sites which inhibit it venturing into shallower waters. This inability to move freely throughout the waters has depleted its numbers substantially, the Fish and Wildlife Service in Maryland estimates that between 1994 and 2004 the population has declined by 50%.

EEL RESTORATION

Luckily, there are several organizations which are restocking the waters with eels such as the Restoration Project which is currently going on in the Susquehanna River Basin, once a prime eel fishing ground, where an estimated 800,000 juvenile eels infested with mussel larvae have been released.. Since 2008, scientists have been helping eels bypass some of the dams as noted in the Bay Journal, “Mussels Could Up a Creek without Migratory Eels”. The Fish and Wildlife Service in Maryland has also been studying the symbiotic relationship between eels and mussels and have also been releasing eels infested with mussel larvae into the rivers to assist with mussel re-population. This can be a truly positive change and can have reverberating effects for the better throughout the estuary water if only the water nutrient level in the shallower waters can be re-balanced and maintained. Thus, the last link in the puzzle is establishing duckweed filtration stations which will purify these estuary waters so the good work of re-population can become self-sustainable.

RE-ESTABLISHING MUSSELS

The first and foremost thing needed is to create nutrient balance in the water. The estuary water has excess nutrients, from faulty septic systems, over-fertilization of lawns and agricultural run off. Since the mussels filter water through their bodies continuously they are very sensitive to this change in water composition. Birdsong Gardens, after extensive research, has formed the Water Clarity Project. Its goal is to use duckweed, a small aquatic plant, which removes Phosphates, Nitrates and other metals naturally from the water which would allow mussel colonies to be re-established in the estuary. Birdsong Gardens hopes to combine their efforts with local mussel hatcheries as well as Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University to repopulate the mussel population both by planting juvenile mussels and by releasing eels infested with mussel larvae into the waters. Once mussels begin to filter the sediment out of the water, their host fish, the American Eel, will be able to be re-established as well, securing the mussel beds for years to come.